Sabin Howard - Sculpting History: "A Soldiers Journey" The Making of the National WWI Memorial

29.8.24

(Hearts of Oak)

And hello, Hearts of Oak. I'm delighted to have a brand new guest with us, only the second artist with us ever, actually, and that's Sabin Howard. Sabin, thank you so much for your time today.

(Sabin Howard)

Thank you for having me on this morning.

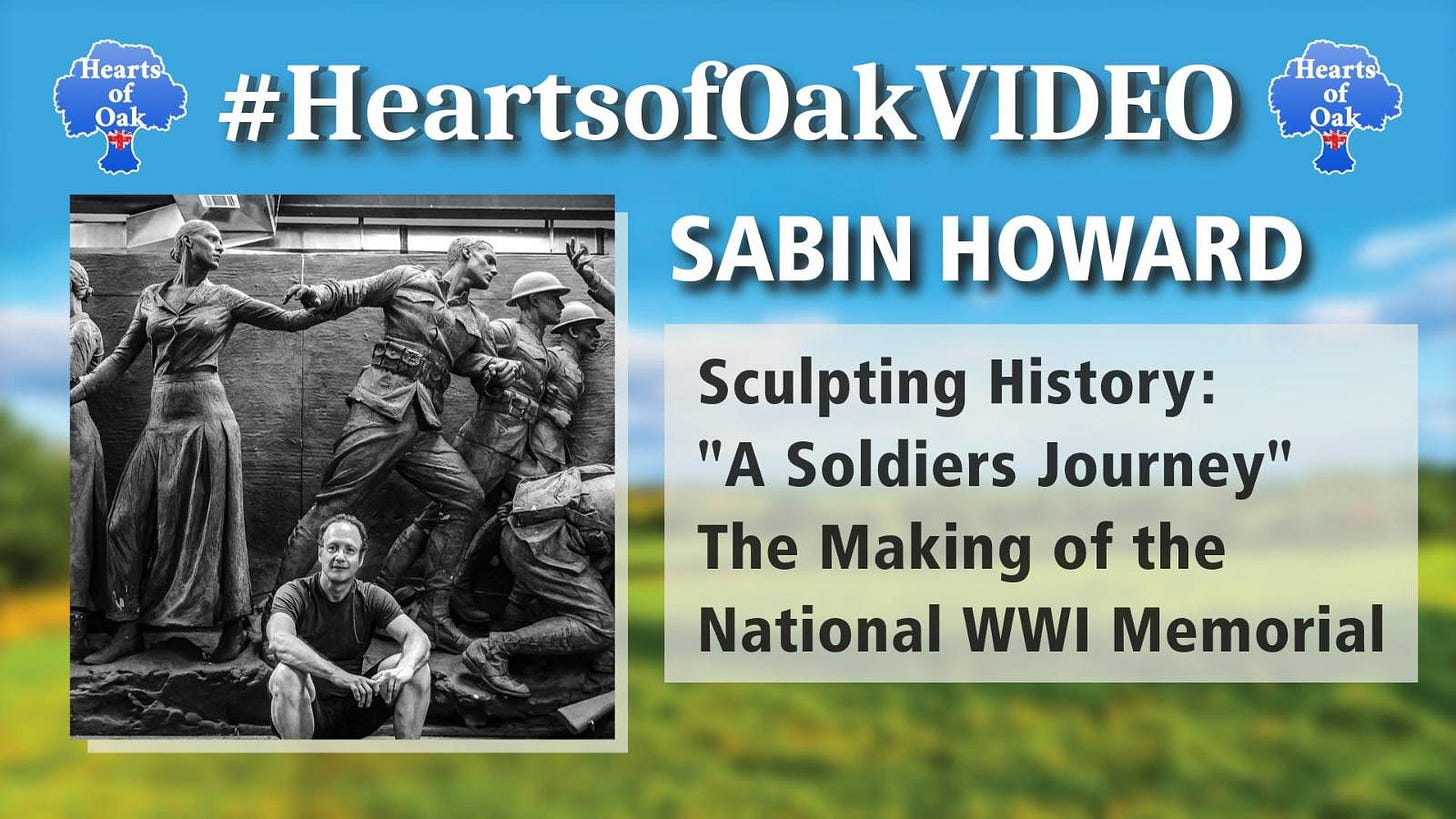

No, not at all. It's great to have you. And thank you to Sam Sorbo for connecting us. And I delved into the work you're doing there with this memorial, World War I memorial in D.C., which is going to be unveiled in a few weeks. It was fascinating. So I've thoroughly enjoyed that. And if people can find you, at Sabin Howard is on X or Twitter, and that's Sabin Howard Sculpture on Instagram and sabinhoward.com. Make sure and go on the website. All the links are in the description, whether you're watching or listening. So do make use of all of those. Now, this sculpture, A Soldier's Journey, years in the making, and this will be the centrepiece of the National World War I Memorial in D.C. It's going to be unveiled in a couple of weeks on the 13th of September. But before we get into that, Sabin, certainly I know the War Room Posse will have seen you on War Room recently with Dave Brat. For those watching not from the War Room, maybe over the UK, they may not know who you are. So could I ask you just to introduce ourselves to the audience?

Sure. I'm a professional troublemaker, otherwise known as a classical figurative sculptor. And I won this competition over almost nine and a half years ago. And there were 360 global teams so it's a blind competition to design.

I jump back and ask give me a little bit we'll get into all that but what is your journey been up to now because you're New Yorker, but you've had time in Italy, what got you interested in the area of art and then how is that career kind of moved forward because I only know one artist and that's my sister-in-law and I don't really understand much from her point of view

I didn't start making art till I was 19 uh and so I really started from zero I went out and bought a book called drawing on the right side of the brain back in 1982 uh and and then I went to an art school I asked them how do I get in and they told me you need a portfolio and this is how low the bar was, I asked them what a portfolio was. So I literally, I had had a lot of experience in Europe. My mother's Italian, my dad's American. They're both PhDs, so they dragged me around to all the cultural sites. And so I only had this vision or idea that art was, you know, Michelangelo, Leonardo, and the greats. I had no idea that there was this, you know, scam going on called modern art.

And I got to this moment in my life where it's like, okay, let's do something here that's a little bit more productive.

And that was 42 years ago. I went through a period prior to this competition where I made very classical esoteric bronzes that came from the tradition of Greco-Roman. I studied in Rome. So that was where I launched off from. And I could say that those first 35 years were almost like this education to then get this project under my belt. It gave me a very clear way on how to operate and problem solve and it also gave me an initiation in the philosophy of what this type of art is I want to make a really strong point here that form aesthetics and philosophy are all one and so you can make figurative art and it can be beautiful and wonderful but it ultimately if it doesn't have a philosophy it's like a Chanel commercial it's really beautiful and so then this this project to me was a huge growth growth learning curve and it was truly an on-the-job training because there is nothing like it out there today it's 60 feet long and it weighs 25 tons and it's 38 figures that are all together telling this one story a soldier's journey so that's that is where we are right now we are counting down the hours before we unveil this to the globe I didn't say the US because it is a global project since we did it in the UK the casting process.

Hearts of Oak:

[5:13] It is and that's a fascinating part of this which I want want to delve in and it's it is so beautiful there is that link between England and the US but I'm for you I read on, might have been Smithsonian website and it had a a review from the New York Times, it was 20 years ago and it said that Sabin Howard, a sculpture of immense talent has created some of the last decade's most substantive realist sculptures. When viewing his works, visitors may be reminded of the times when sculptors like Donatello and Rodin walked the earth. I mean, my question is, before we jump into this more, how do you kind of measure success of your projects? You see a review like that 20 years ago, but obviously held in huge regard. But how do you kind of measure the success whenever you have an exhibition or do a piece?

It's very funny you would read that quote. The New York Times then wanted to rescind the writing of that critic because when they saw what I did, they were like, no, we don't want him. Scratch him. He's not what we promote. boat so it was that but that was an initiation also an understanding like okay wow you're really doing stuff outside the art narrative. I don't know how to explain it, it's like I had this myopic single-minded vision for all these those years and then I got towards the end of that cycle the 35 year cycle of sculpting in the studio with you know male nudes mostly and doing these figures that were, for the most part, no larger than a meter in height, half life size. And it was like, nobody's paying attention to you except your clients, which, you know, they'll buy these sculptures and put them in their private homes and dwellings. But I wasn't getting past that. And I saw that if I did that in the future, it was like spinning my wheels in the mud because I would go down in history as a no one. and so I really wanted to make a difference and I knew I had.

Look, people say you're very talented, but I beg to differ. I think that I'm very persistent. I think that my persistence is off the charts, and I think my talent is pretty good, but it's really this burning passion and fire to actually change and make something of value you, for not the elites or the art world, I was asked recently, how do you think the art world will respond? Will they say it's kitschy? And I was like, I really don't care what the art world thinks because it's not for them.

I made the sculpture for really veterans and for people that come to Washington who are not necessarily art aficionados. I mean, how many of those people People have gone to like the V&A. It's like not many. So it's the whole parameter of what the art stands for and who it's for. It doesn't jive with the art world. The art world is full of nonsense anyway. They've been doing the same thing for the last hundred years. It's redundant. They should be fired. And so it's like I really stepped into a void here, a very strange moment historically, because it goes along with a lot of the things that are happening politically, where you have this really huge, huge fight between populist people and governments or elites, and they don't want to relinquish their power. And so I'm making a sculpture that's very empowering for people and returning art to its rightful owner Which is you know your everyday Joe who who takes the subway or the Metro to work? It's like those people deserve to have art that elevates them and speaks of higher consciousness so I'm very I'm very proud of that fact and that's why I'm vociferous about that.

Because you've gone from, yeah, you mentioned about views, and I know whenever you've done one of the interviews, you talk about cancellation, and one artist we had on who we've got to know had a lot cancelled because of his views, that they weren't on the right side, and they weren't accepted, difficulty getting venues to have exhibitions, all of that. What is it like for you? You know what you think. You've got common sense views, which rhyme probably with the common sense majority, the silent majority. But have you kind of just got on with your art and you keep your views to yourself? Or have you used that position to actually speak when you see things you think are incorrect or injustices?

It's a very, really interesting thing because the sculpture is 150 yards from the White House. So this is like you couldn't have asked for a better location in the U.S. The visibility is massive. On that note, who is my biggest fan? The WarRoom, Steve Bannon.

And what a fan to have in Steve.

Yeah, I mean, it's like a very honest guy who actually plays forward art that is about the movement that we just spoke about. But it's like, I got one, let's call it mainstream media, it's Sunday mornings on CBS. But the lady there, Faith, was very excited about what I'm doing. So I'm not really seen as, I mean, maybe I'm speaking prematurely, but I haven't been canceled because I don't speak about my art politically, as you notice. I speak about it in terms of art and the necessity to make something sacred. And so do you really want to cancel that? That's like saying, let's cancel our nose. So then you'll cut your nose off your face. I'm not going I'm not venturing into the political realm yes I have you can tell immediately I have strong views but look the word conservare from Italian or Latin is to conserve so I'm conserving sacred values traditional values I had a very strong education before I became an artist I was a lit major which that didn't go anywhere because I quit you know I saw that was a dead-end street read, but I read a lot of books and I really have a...

You can't make art without having something to speak about. And so, yes, you need the technique, but if you don't speak about something that's universal and yet at the same time also individualistic to your own experience as a human being, you're sunk. And I think a lot of the stuff that we're seeing today is it's all about like esoteric cryptic messages created with very ramshackle methodologies of craft. And I'm very much for the rigor to study, to learn how to do something really well. So when people look at it, they're like, oh, my God, that guy's a master. But I'm not searching for technique. This is part of the process. At this point, the technique is like it's part of my unconsciousness.

And then so now it's like my experience as a human being is starting to come out, especially in this project. I couldn't have done this project in my 20s. I'm 61. I've been around a block a bit. I've really taken my fair share of lumps and bumps along the journey as an artist, as you can imagine. I mean, my studio was in the South Bronx, East Harlem for over, you know, 20 years. And so I'm used to a harder life prior to this. And I'm, I work, I like to work. I haven't sculpted for nine months and it's like outrageous for me after this because that's what I'm supposed to do. So I'm really looking forward to getting back on another one and doing another really big project. And my wife made a documentary because she's making it. We had a camera rolling throughout the whole time. And I wrote a book that's 750 pages that I will launch in the spring. I just believe that if we don't speak up now, we're going to run into trouble. And it's better to get into trouble now than not even have the ability to get in trouble later. That's why I'm on your show.

All right. A hundred percent. I understand you entered the competition back 2015. So you're getting nine years, most of a decade. What's that process there were hundreds of others who had applied, what was the process of you deciding, actually I'm going to do this, which was made different than what you'd done before and also you have to put together a a fairly substantial proposal I assume, but what was that like, what made you want to actually enter that competition and what did you feel when you got that call to say actually you've won.

This is a really interesting question, so you asked me me, how did I get to that place, right? I'd never done public art before. Okay, I did a sculpture in 2011. It was an Apollo figure, a nude male life size. I spent 3,500 hours with two models, and I made something that was the highest level I could possibly do, and I wanted to make something that was on the level of Michelangelo's David. So then I go out and get this gallery in Chelsea, which is a gallery district in New York City. And I emptied this room. It's full glass walls with a little help from a few people. I put up all these lights and I showed my whole body of work that I'd been working on for a hell of a long time, 30 years.

What happens? Nothing. Big zilch. And I'm like, okay, Sabin, you need to do something different. This is too esoteric. You're not reaching anyone of substance. And then something happened there that this man from the Institute of Classical Art and Architecture came in, and he saw the work, and he said, wow, this is amazing. Let's move your stuff over to our offices after this show. And I did. And then I launched a book there that my wife and I had written. And then something, you know, how the universe works. Well, this man, Frank Gehry, asked them, ICAA, if they could put a list together of sculptors that could work with him on the Eisenhower Memorial.

So I get a call or it was an email from Frank Gehry. And please come out. I didn't know who Frank Gehry was. And I end up in L.A. at his offices. And he's like, well, you're our number one on our list. And we want to hire you to make the sculptures for the Eisenhower Memorial. It went afoul after three months. They liked my ideas very much. But we were in complete opposition ideologically. Frank Gehry is about chaos and a modernist. I am very traditional, and I believe the universe is unified.

So it's like just parted ways. But the bug was in my head. I got another email in 2015 from Justin Schubau at the National Civic Arts Society in Washington, and he says, do you need to enter this? I enter with an architect down in Texas. We don't make the final five, but in my gut, I'm like, this is not over. I'm going to, something's on.

And of course, and in September, Joseph Weishard, this young architect in training, 25 years old, sends me an email, would you partner up with me? And it's truly a gift from God, because if I had partnered up with any architect that was more established, I would have been put hierarchically farther down on the ladder. But with Joseph, Joe, it's like he was like, gave me full potentiality. And so it was like, I'm truly the focus of the park. It's a whole project. And that doesn't happen these days. And it set and established a paradigm for proceeding forward. And that's why the sculpture is so powerful and large and magnificent and epic, because I was given the ability to come up with something. Also with centennial commission they're the ones that ran the project um that yes there was a committee ideologies in centennial commission that was phase one but overall they were like keep showing us stuff and when we like it we'll tell you and i did 25 iterations over nine months.

That doesn't happen normally, and also normally it doesn't happen that an artist can be that brutalized by a committee. So I would keep coming back, every meeting dejected, getting back on a five-hour train ride, back to my South Bronx studio, and then come back with another vision, and I kept ramping it up to a higher level. And then we had to go through the Commission of Fine Arts, And I had established, I guess internally with Centennial Commission, that, yes, you have really reached the best of what you can produce. And this is it. So I didn't budge. And I was stubborn, really stubborn with Commission of Fine Arts.

And we got through finally after a year and a half, which is lightning speed for these experts in art. I mean, imagine bureaucrats being such experts in arts. They never looked at a sculpture before in a museum. They're all landscape architects. They all sit behind this wooden oak desk. All academics, never done anything in the real world, always working in the ivory tower. You can tell where I'm coming from, given the fact that both parents are PhDs.

And they don't have a connection with reality. And we got through. This is, it's truly a miracle that we got through and that's how this happened and then I had to, you know get this produced that's a whole nother voyage.

I want to play, there's a just a one minute video clip.

Sounds from the foundry

I wanted to play it with the sound because you feel as though you're there. You can feel the intensity and the hard work. But that was you had to find a foundry in England. How did that come about? Why was there nothing in the U.S. that you could find that suited your purpose?

I was given, after an argument, three months to go on the road and find the place that would put this together. How much, how and where, so I looked three months in the US, I went all over, I saw 40 foundries and they all had the same concept for the most part, we have this way of doing things and they would cut things into one foot panels and then assemble it and I was like, no you can't do that, I need large castings, I don't want all these pieces, fit back together and then your welders and finishers redoing my texture. I'd like to minimize that. A week out and I have to present something and I had someone in Berkeley California, he was run by an Italian, so I said all right fine, I'm going to use him, I'm looking on Instagram and I come across this grizzly bear and it's called indomitable and so that I look at the man's name who made it. It was Nick Bibby and so I just sent him an Instagram message said Nick, where the hell did you sculpt this? This is amazing. And by the way, I'm Sabin Howard, great fan of your work. And we arranged a phone call. We were on the phone next morning for an hour and a half. And yeah, and Nick tells me about this foundry. I'm getting goose bumps talking to you about this. So then I get off the phone and I call up Pangolin in Cotswolds.

And I get on with Steve Moll. He's the foundry manager. And I dropped this bomb on him. We need to make this 60-foot long 38-figure composition. And he's like, you know, very calm and collected in the usual UK fashion, not showing any emotions. And brilliant. And we have this conversation. I'm on a plane in the next few days. And I walk in to this industrial complex. And I walk up the ramp to the reception desk. And there on the reception desk platform, you know, where it subdivides you from the receptionist, is this funny thing, a bronze skeleton of a dodo bird, an extinct animal.

It's incredibly cast. The craftsmanship is brilliant. And it's dynamic. It's kinetic. It's walking. It's moving. So just think about this. The whole skeleton was moulded, reassembled, and cast. And it's incredible. And I'm like, we've arrived. This is the place. I never saw anything with that amount of craft in the US. And the whole thing went to the next level when I was given the tour. And met Rongwei Kingdon, the owner of this foundry, because he said, we work with the artist. Whatever the problem is, we create a solution. It's, yes, thank you. That's what creativity is, problem solving by throwing, you know, all your different tools at it. And they have four different ways of casting, 200 people.

And it was a Godsend that I ended up there because, you know, we got hit with that thing called COVID. The thing that was supposed to wipe out the planet and so they couldn't come to the my studio in New Jersey to make the moulds and so I had to trust them and we ended up shipping literally, shipping our original clays, cutting them up and putting them in the shipping container, all buttressed with this framing system across the Atlantic ocean. 3 000 mile trip on trucks and ships, nothing got damaged and and then I didn't see the bronze in its assembly because I couldn't. We were in lockdown and they did everything correctly off of the the smaller models that we had made andI'm eternally grateful to that to that source of inspiration and creativity because, this is rare, I even think, for the UK that you get people that are so devoted to craft. And really, it's generational because they have grandchildren of former founders that began 40 years ago. And so it's being passed down almost in an apprenticeship system.

That's a really magnificent thing that needs to continue in the arts. I think people don't realize how important and invaluable the arts are to our culture. I'll tell you why. Sorry to be rambling about this, but... Arts are not real. They are a translation from the real world, but they can show us what's possible. And so that's why I made this project, and that's why it got cast there. And they were rather sad when it was completed and then cut up and put into two shipping containers and shipped back to the US. So now my mission, according to Runway, is find another project. That's my mission.

Find another project like this to bring it to Pangolin.

Well let me pick up on that in a moment, but I want to ask you, I mean few people will have a single project that is this length of time, that conceptis alien tomost of us, tell us how you were, you talked about yourtenacity and just getting pushing for what you want and not giving up and25 times of presenting, I choose that but it's such a long, were there times there must have been times where you thought I don't know if this is actually going to come together

Yeah, the not coming together part really only happened when I had to sit in front of those bureaucracies because you win a contest and so you have been empowered or commissioned, you're in charge of that project and the agency such as Commission of Fine Art is there to ensure as a regulatory commission that you achieve the correct standards because of the nature of the project, that it is a representation of our country on a very large scale.

100% correct. Great. Great idea. But as all things in government, there's a difference between real world and what actually happens. So these government officials were all landscape architects, and they did not want to see this project proceed. And whereas anything in D.C., real estate, any real estate in D.C. Is the most highly contested real estate on the planet. It and so they wanted, oh yeah we're going to make sure that that sculpture is as small as possible and maybe we can make it like five mil in length or something or let's make it vanish and they did everything possible to minimize it and I mean I'm not joking when I say this one of the commissioners said, let's just turn around the wall and have a fountain in the front and the wall could face the back of the park which were steps 10 feet away now. You'd hear this kind of crap, meeting after meeting and it wasn't a joke and so then we did get through and I can't tell you why, but you know how everything gets through in government so you can figure, put the puzzle together yourself.

That was, I got sick one month and I lost 25 pounds from the stress. I went back and they were like, wow, what happened to you? You must have cancer or something. They wish I did.

They wanted to see me go away. And I became, I didn't make friends on the design committee either because they were like, well, you're not listening. I did not make friends with the Centennial Commission. I actually told them to, you know, F off at one meeting, literally. Stood up and said, I don't care. This is a national memorial. I will be true to my art. I know that I can't live with myself after all these years if I don't produce something that is true to myself. I can't live with myself. I take a bullet to my head first. And literally, I want to wake up and say, okay, let's go again. Let's do this again. One more day to studio. Every day I leave the studio and I feel very like a failure. And I think this is kind of what makes my art what it is. I show up the next morning and I'm like raring to go a little bit more optimistic. By the end of the day, I still think I'm a failure. I did this project. I look at it and I'm like, I wish I could have done this to make it better. But that's the mind of someone who's creative. There's always, you can, you constantly grow, you constantly. So you don't want to like giving up and handing your power over to others is the worst thing you can do for your growth pattern as an artist and a human being. It's disaster.

To understand about the war side and other monuments living in London for the last 20 odd years, you fall over monuments. And statues of different events and parts of history, certainly in London. And I was, this to be the National World War I, I know there's a World War II large memorial there in DC. Is this the first one that's been done? I mean, it's 100, what, 106 years after the end of World War I. How has it taken so long? Are there other World War I memorials, but this is the actual official, is this the first one in DC?

Well it's our country, only it wasn't like England and it was a punch in a nose for us 115, 516 deaths, okay yeah serious stuff.

1.3 million, I think

Yeah and and how many casualties after that, you know probably pestilence and uh, 22 million people die in Europe and Russia. It could be more. It could be more. Those are approximations.

Catastrophic moment globally. We're still feeling it because you go from a Victorian era and the idea that there is God to now this nihilism and the idea of chaos, like Frank Gehry versus Sabin Howard, chaos. Modernists come in.

Then and you have who the nihilist and existentialist philosophers spring up out of France and it's literally, they're saying there is no God and so you're responsible for your own life and no one else and and you are not attached to anything else. I seriously think that it has wreaked havoc and I see this because I go to urban areas and there's such a disconnect between people. And the end result is there's a lot of mental health issues today in our society because people are not in community. And the government is also trying to establish more of a disassociation between us as a race and a populace. And that is a direct result of what happened in world war one, so the project was very important once I began to understand this I didn't read a lot of books about it but I started seeing a lot of images and the image, I'm a visual artist so the images really spoke to me on a very deep level, in the beginning if I had this conversation with you I'd be I'd be sobbing, I'm sorry but it was like people would think I was, like batshit crazy. It's like, I'm not, though. It's just being put into this situation, and you're feeling it, and you have to sculpt it correctly.

And that's why it's really good because it's emotional, it's human, takes you to that place and the artists that had done a memorial, there's one in, a national world war one memorial in Kansas City, that one is not on the mall, so now there are two, there's one in Kansas city and there's one in in in Washington and it takes its proper place And imagine this, we went backwards. We went from Vietnam Memorial to Korean War Memorial to World War II Memorial to World War I Memorial. And now it takes its proper place. And we have an amazing spot, actually, because we are surrounded by classical buildings. things were, like I said, the back end of the White House, 150 yards away, the Willard Hotel. These are all very classical structures, and it's a very odd park to begin with, but it makes it sacred now because it's lower than street level. You take stairs down to a plateau, and then that plateau is 175 feet with distance to view the sculpture up close up to five feet so you have two experiences one is like the full thing and then one is the intimate view of all these faces that were actual veterans um that had combat um had been in combat and that's amazing to me.

What effect did it have on you? Because to actually spend 10 years of your life looking at a very dark period of history, the first war that was a global war, and you've mentioned over 20 million deaths affected every country. In fact, I think 1918 is the only year where the US population decreased in the last over 100 years. So devastating effect. And for you to focus on that, because part of it, you're not telling the numbers, you're telling the personal stories with those images. So you kind of connect with them. You begin to, I guess, relate to these individuals, these people that you're actually casting and putting up there. So how did it kind of affect you individually?

I started to get going on a project when I looked. I actually Googled images of World War I. And I found all these images of like young people. One of them was a train at a station and there were all these men all jolly on the train with their heads and arms out the window and all their girlfriends and fiancés on the platform. And the girls reminded me of my daughter who's 34 and some of the blokes that I know, you know. And I realized very quickly that this is not any different than today. It's another generation, but we continue to throw human life into war, now these never-ending wars. And the war that was supposed to end all wars was actually the launching point to kick off for wars that never end. So the military-industrial complex can just continue. Like, what happens if Ukraine ends? They'll just start another one so they can keep the money belt rolling towards the arms industry. streets. It's made me very, very cynical as a human being towards government and made me very deeply connected to humanity.

That is the change. And I'm smart enough to know that don't stick your neck out and speak about political issues because then your voice will not reach others. And so what I just said, if you take that and translate it into political terms, you know exactly what I'm saying. And I don't have to speak those words, you can fit the pieces together. And so I am saying, guys, you need to go and make a change when you go vote, because you need to protect your citizens. You don't want to put them in jail. You want to protect them because the government.

This is not the way I used to think before, is supposed to be a civil servant for the populace, not vice versa. And that's the change that happened to me as an artist because basically prior to this project, I had visions of the Renaissance, and now it's like Renaissance today. It's like this is, for me, the moment of an awakening, and the sculpture, I call it, when I give the acceptance speech and presented to the public as the American cultural renaissance. This is the first piece of many to follow and a movement towards that. So that is actually the catalyst that changed me and made me who I am. You can't ignore that many deaths and then realize, wow, this is still going on. I did grow up in the Vietnam era, after all, and that's the same thing.

And something like this is so essential at a time where certainly if we look at the education system, where children here in the UK were rewriting British history to the British Empire, the largest empire the world has known, actually, that was all negative. So let's just focus on that. And that attack on our history, and I think that's why something like this is so important and essential, that you can stand there and you can take it in, actually, what these individuals did for us.

Yeah, there's 5 billion people that make $2 a day or less on the globe. So if you take into your country even a million a year, You know, it's devastating for your country, but it won't change a damn thing externally. It's not the solution, but it is the solution if you wish to destroy countries that are more put together. And this is what we are fighting at this moment all over the globe.

Can I ask just to kind of begin to finish about the parts of it? I think there are four scenes. The first scene is him answering his call to duty and going. And then scene two and three are there going into battle, the battle scenes. And then scene four, he comes back, I guess, a hero from being away. Tell us kind of about those four scenes, because that's the story from before, then in the middle of it, and then coming, returning home.

The template is the hero's journey. And it's a cycle of leaving home and returning home. And what happens in the middle is the battle scene, which is the transformative moment. And then you need to show the transformation, which is the shell-shocked soldier at the three-quarter mark. So I used the same model. He appears five times across the tableau, moving from left to right towards the future. And the Alpha and Omega, I used my daughter. And actually, this is odd, because the World War I was four years. And then my daughter was used to also show that growth. And a human being, I sculpted her head back in 2020, and again in 2023, at the very end of the year.

At the very last thing I did was, my daughter and, this is a generational thing of how it affects not only the military but their families and their parents and their children and offspring so the middle scene is the most, it's insane, the kinetic energy that I placed into the battle scene, it's just an explosion of animalistic charge forward, led by the dad who's the very central figure of the whole wall in an open chested arms splayed screaming face going forward since, and then all of a sudden, what's after that the cost of war, which is the focus of this sculpture, there is a nurse helping a gassed soldier who's blinded and crazed and it just lost lost it and she is the one holding him and lifting him. And then the shell shock soldier was, I used a ranger for the face and a Marine for the whole body. And then another nurse who is very powerful. I used a bodybuilder for her and a daughter of a Colonel for the head. And she is also carrying a soldier, but that's the focus that three quarter mark, not that you'd know, cause there's so much stuff happening on this wall.

It's very poignant. What I needed to do was make it feeling heavy. And then that's how you get people that aren't into art. They're like, wow, that's really emotional. And there's a lot of significance here for them. You have to make stuff that's significant to others. I worked in service of and I don't think a lot of people in the art community are in service of something greater than themselves, that means to work for the sacred, this sculpture is sacred, it will be treasured I believe, it's a funny thing for me to say because I never thought of myself as being that special and then all of a sudden you make something that's like very unique to the country, actually to the globe, it's very unique, I'm sculpting traditionally, I'm not using the computer or photographs to do the final sculpting. I use them to get through the grunt work in the middle at Pangolin. And that's what makes the difference because of my training and then playing the training out. I fired everybody and ended up sculpting just as one assistant at the end.

And to present that, in effect, you presented to the nation. It's not just to clients or individuals. It's the nation. That's, I guess, quite a weighty responsibility.

Responsibility, yeah, yeah, it's what you were saying before, history is the umbrella that binds a culture and a country together and so remembering the history of that country is a way to unify not fracture the populace that's a weighty responsibility I didn't have that sense and while I'm sculpting, it's like I have so much internal pressure to perform, the competition is always internally, like how good can you be every day so you know you, just that's the pressure, it's internal and I can live with that because it doesn't, that didn't change from the way I sculpted prior, I never really thought about the external, of the pressure to perform for others, no just do it for you, do it internally and it'll come out just fine, get in the process, don't think about our product. And that always works. Process is what carries you through and gets you to five o'clock or whatever time you're going to knock off and then come back and do it again. Be well rested and do that process again.

Now, obviously the WarRoom Posse. Whenever they go to D.C., they'll be able to see this.

I'm looking forward to next time over, actually seeing this. But you mentioned about the documentary and the book. Maybe touch on that, because not everyone can necessarily be there in person to see it, but you're making it available through other means, not just the physical mean, but through book and film.

The book will be called Born Cancelled. okay and I'll explain. I feel as an artist that you are kind of picking a life that is not following the herd and so, then you're already kind of like coming up with your own ideas, which will get you into a heap of trouble and basically I was born cancelled because of that And so then, sure, cancel me. I don't care. I'm already cancelled in my mind. So the book is very, I really spoke the truth about what happened and how the art world has failed miserably and is buttressed up by a financial system. And the movie, my wife was a novelist prior to this, published in 12 countries, a bunch of bestsellers, she knows about storytelling, that will come out in the spring and I don't know what she's going to call it yet, but that project will be amazing for people to see behind the studio doors, it's not like we hide anything,, it's like you can see me go off on people and just fire people left and right. It's like, I think I fired seven people throughout the project, and I only had one man standing at the end was Charlie Mostow.

And I think what happened is, within the studio, it's like people couldn't understand the idea of being in service of. And the ones that remained behind and stayed with me were those that got it, that we weren't doing this for ourselves. We were doing it for the betterment of others. So that those should be out in the spring and I'm very excited to share those with people.

I look forward to that. Obviously, the unveiling is 13th of September, just in weeks, and book and documentary to follow. I'm assuming that you'll take a breath when this is done, nearly 10 years of your life, and then you'll move on to something else. Do you have any ideas of what the next calling is, or will you just be so relieved to actually finish this that then you can think then?

I've been thinking for the last nine months. I'm done thinking. I hate living with myself. I like working.

I can't wait to jump into something. And we have an idea for an American history project that's equally as grand. It would have 35 figures passing through an arch led by Lady Liberty. That's what I'd like to do. We have a big moment here. We don't know our political system. November, we elect a new president.

Oh, yes. We're all waiting with bated breath here and praying. Yes.

That is a big moment also because I would be connected to that administration, perhaps, to do monuments for the country. But I'm looking more towards private sector right now to get this project made. And it's really a two-year process to make a really good model because that's the designing the creative aspect scout snipers was another project that's been awarded but again finances and then it just really depends who comes to me once the sculpture is in place I need to sculpt again it's very very important for my well-being I don't do well not sculpting I mean I sculpted for all those years and then all of a sudden you do a big project and it ends it's like your head goes slamming into the windshield at 90 miles an hour so that's why I wrote the book, but now we got to get on with it, we need to crack on as you guys say.

Crack on, well and we look forward to that being unveiled in weeks. A Soldier's Journey, the centrepiece of that national World War One memorial